On Being Vulgar Middle Class

Jealousy, poverty and inheritance money

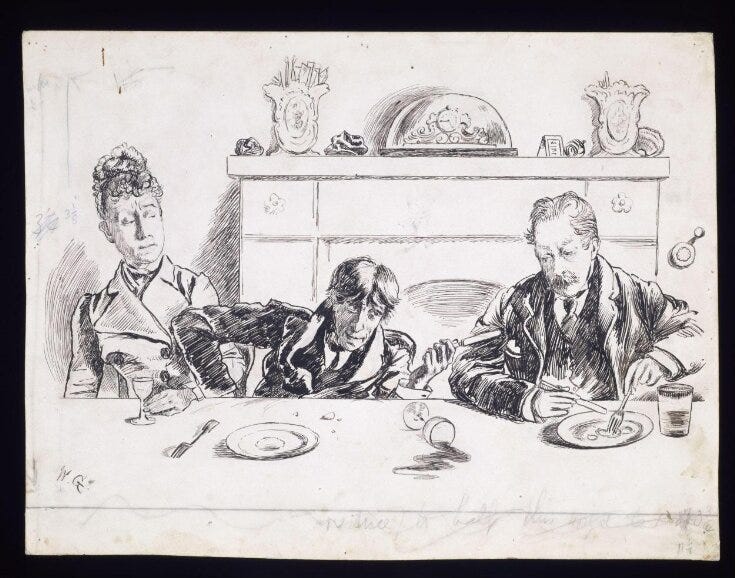

Two days ago I had the misfortune of finding out that an old friend of mine, who I hadn't seen in some years, has done very well for himself. The fact was related to me over dinner, and in such a way that I was expected to congratulate him. He had bought himself a house and — what’s more — in an enviable neighbourhood of London. No sooner had he told me of his success than I began scurrying around my mind looking for immaterial ways in which I might have said to have bettered him. Had I not, after all, studied literature where he had studied accounting? And did I not better understand Beauty? And had I not the art of rhetoric, with which even the most pitiable circumstances may be bent to a more pleasant reality?

But his is an old Catholic family, and Catholics tend to run into money one way or another, even when they are perfectly idle or stupid. This person is neither, and so I cannot even fault him that. He has spent the several years following our graduation scrimping and saving, and establishing himself in his chosen profession, while I had spent mine trying to learn enough Spanish to read Don Quijote, cooking Duck Confit and writing think-pieces for marginal right-wing publications.

The difference between his family and mine is that his has learned to be rich over a long course of time, while mine is still reeling drunk from the first hit. I have become acutely aware of the unusual and historically novel position which myself and the other children of the new vulgar middle classes, children of Blairism, find ourselves in: That the wealth and comfort of our parents has afforded us idleness in our twenties and assured us financial ruin for ever after. We lack both the discipline of the real middle class and the skill of the working class, having neither the education, connections nor skill necessary to sustain us beyond our twenties. We spend our youth in a temporary and cheapened aristocracy, working little, pouring our time into half-baked philosophising such as this, before tumbling into our thirties poorer and more wretched than the sons of bricklayers.

We have been bred, quite simply, for pleasure. We are soft and useless, but we are at least exempt from the sort of suffering that real people experience. The thousand mild nuisances of middle-class life are, in their total sum, a greater suffering than the few but acute miseries of the poor. We suffer neither, suspended in a reality which asks nothing of us. We are not even expected to recognise the pathos of our condition.

I discovered later that my friend’s investment had been made with a substantial advance on his family inheritance, and was reminded of that small lifeline which exists to almost all of us children of the vulgar middle-classes: That of death. Not our own, but that of our parents and our grandparents. When, after ten to twenty years of desperate poverty, that black day comes, we will be buoyed to the surface, now on dry land, now grieving. But we will be the last benefactors. Our children will have childish, whimsical parents. They will be made to read Shakespeare, and go to the theatre, and eat duck confit. When we release them into the world they will be as useless as we are. But with the inheritance dried up they will be forced to work. They will have industrious and intelligent children, who will in turn give them idle and feckless grandchildren. I hope that in a century’s time those grandchildren will take some comfort in these words. I hope they are at least amused.

Haven't felt so naked and exposed from a piece of writing in a long time. Thanks.

The problem is me and my boyfriend, whom i intend to marry, both of us belong to "Vulgar Middle Class". Still chasing the goose out there somewhere, wanting desperately to come out of it and buy a house "in one of the enviable neighbourhoods of India".